Vladimir Putin KGB Agent 1975-1991, Director of the KGB/FSB 1998-1999

Marcel H. Van Herpen

This book examines Russia’s “information war,” one of the most striking features of its intervention in Ukraine. Marcel H. Van Herpen argues that the Kremlin’s propaganda offensive is a carefully prepared strategy, implemented and tested over the last decade. Initially intended as a tool to enhance Russia’s soft power, it quickly developed into one of the main instruments of Russia’s new imperialism, reminiscent of the height of the Cold War.

Marcel H. Van Herpen

This fully updated book offers the first systematic analysis of Putin’s three wars, placing the Second Chechen War, the war with Georgia of 2008, and the war with Ukraine of 2014–2015 in their broader historical context. Drawing on extensive original Russian sources, Marcel H. Van Herpen analyzes in detail how Putin’s wars were prepared and conducted, and why they led to allegations of war crimes and genocide. He shows how the conflicts functioned to consolidate and legitimate Putin’s regime and explores how they were connected to a fourth, hidden, “internal war” waged by the Kremlin against the opposition. The author convincingly argues that the Kremlin—relying on the secret services, the Orthodox Church, the Kremlin youth “Nashi,” and the rehabilitated Cossacks—is preparing for an imperial revival, most recently in the form of a “Eurasian Union.”

An essential book for understanding the dynamics of Putin’s regime, this study digs deep into the Kremlin’s secret long-term strategies. Readable and clearly argued, it makes a compelling case that Putin’s regime emulates an established Russian paradigm in which empire building and despotic rule are mutually reinforcing. As the first comprehensive exploration of the historical antecedents and political continuity of the Kremlin’s contemporary policies, Van Herpen’s work will make a valuable contribution to the literature on post-Soviet Russia, and his arguments will stimulate a fascinating and vigorous debate.

Christopher Jon Bjerknes

On 16 August 1999, the Duma elected Vladimir Putin Prime Minister of Russia. He faced enormous opposition to his rule. On 26 August 1999, Putin began to attack the Chechen People on the pretext of suppressing the activities of the Islamic International Brigade and in response to the "Apartment Bombings" which Putin blamed on the Chechens, but which were in fact the work of the KGB/FSB. These international terrorists were working for Putin, not against him. Putin rapidly gained the popularity he was initially wanting and used it to elevate himself onto the lofty throne of a new Russian dictatorship. His feet barely reached the ground. Vladimir Putin quickly restored the communist dictatorship of the Soviet Union with covert State sponsored terrorism which provided a pretext for ever expanding State powers. Putin took over control of the media and persecuted dissenting journalists, thereby insulating his communist kleptocracy from public scrutiny. Vladimir Putin has used Chechen terrorists as a pretext to invade Chechnya, Georgia and Syria. In Chechnya, Ukraine and Syria, Putin has pitted Chechens against Chechens to intensify the fighting and amplify the destruction. Where the Chechen terrorists go, Putin and the Russian military follow, and occupy. Reconstructing and expanding the Soviet Union as he goes, Putin has since followed the Chechen shock troops he commands all the way to Syria, where they lead ISIS. These same terrorists strike around the world at key moments in the election cycle of Putin's favored political candidates abroad, candidates who run on an anti-terrorism platform and benefit politically from the terrorism they ostensibly oppose. It is a generally unacknowledged fact that ISIS strikes in regions and at times which benefit Putin's preferred politicians abroad and at home. This cannot be a coincidence, given the numbers of attacks and their predictable effects on elections. But the author is alone in reporting this obvious fact to the world. Putin and Trump are colluding to subvert and co-opt NATO and change its mission from defending Europe from Russia, to fighting self consuming wars against Muslims -- destroying their countries and the West for the benefit of Russia and Israel. The book exposes the hypocritical role neonazis play in undermining NATO and promoting KGB communist Vladimir Putin, and Putin's hypocrisy in supporting "fascists" abroad while outlawing Nationalism and anti-Semitism in Russia. It provides a history of the controlled opposition of Libertarianism to Communism, as well as Murray Rothbard's anti-American Soviet apologetics and Ron Paul's revealing Russian apologetics. Ayn Rand is exposed as a communist and zionist subversive, and member of the Soviet "Trust". Trotskyite neoconservatives commandeered the Republican Party, and in collusion with Russia and Israel have forwarded the Marxist permanent revolution worldwide with false flag terrorism and endless wars. Given Americans' reluctance to fight more self-defeating wars against Islam, Putin now carries the torch of Trotsky's permanent revolution and engages in relentless false flag terrorism. He seeks to turn all of Europe into vassal States serving a new and enlarged Eurasian Soviet Union. The communists are staging conflicts between bolshevik antifa and their neonazi twins so as to destabilize the West to the point of a crisis, at which point the communists will instigate civil wars and invade. The communists never stopped fighting WW II and seek to genocide the German People as an act of revenge and a means to prevent another counter-revolutionary war against Russian bolshevism. There is a large section on the British 2017 general election and the spate of terrorism that took place leading up to it. The Soviets created the modern anti-zionist movement and are using it to promote Muslim immigration to Europe and America, and to drive a wedge between the North Atlantic alliance and Israel, in favor of a Russian-Israeli alliance.

David Satter

In December 2013, David Satter became the first American journalist to be expelled from Russia since the Cold War. The Moscow Times said it was not surprising he was expelled, “it was surprising it took so long.” Satter is known in Russia for having written that the apartment bombings in 1999, which were blamed on Chechens and brought Putin to power, were actually carried out by the Russian FSB security police.

In this book, Satter tells the story of the apartment bombings and how Boris Yeltsin presided over the criminalization of Russia, why Vladimir Putin was chosen as his sucessor, and how Putin has suppressed all opposition while retaining the appreance of a pluralist state. As the threat represented by Russia becomes increasingly clear, Satter’s description of where Russia is and how it got there will be of vital interest to anyone concerned about the dangers facing the world today.

Alexander Litvinenko

In Blowing up Russia Alexander Livtinenko and Yuri Felshtinsky vividly expose how the KGB’s spymasters were able to survive the collapse of Communism. Then in 2001, in a plot like the burning of the German Reichstag, lethal methods were used to catapult Vladimir Putin into the Russian presidency. Blowing up Russia is the first book to be banned in Russia since 1974.

Alexander Litvinenko was killed by FSB secret agents Lugovoy and Kovtun in 2006 in London with polonium-210. The order for this murder was given personally by Putin.

This book and documentary movie are banned in Russia.

Alexander Litvinenko

Alexander Litvinenko was a member of Russia's FSB, its secret service formerly known as the KGB. Claiming he was ordered to assassinate a Russian tycoon, he was arrested twice before fleeing to the UK. There, he spoke and wrote frequently against what he called the "mafia state" of contemporary Russia under President Putin. Litvinenko was murdered with radioactive poison in 2006 in London. This collection of writings and interviews -- curated and translated by another daring dissenter, Pavel Stroilov -- lives up to its title, making one claim after another against the FSB and the regime which Litvinenko fled

Yuri Felshtinsky

'Impressive.' TLS 'Dodgy deals and horrible murders.' New Statesman Book of the Year 'Explosive.' Daily Telegraph Welcome to the Putin Corporation. Russia's March 2012 presidential election showed that Vladimir Putin's position is unassailable. Why is he on course to lead Russia for a longer period than Stalin? Is Russia experimenting with a new form of tyranny, where the whole country is run like a business for a small group of shareholders? Based on meticulous research, The Putin Corporation investigates the intimate relationship between Russia's oligarchs and Vladimir Putin. Why do they allow their economic, financial, state and business interests to be run by a man who was in Soviet times an obscure KGB officer stationed in East-Berlin?

Karen Dawisha

The raging question in the world today is who is the real Vladimir Putin and what are his intentions. Karen Dawisha’s brilliant Putin’s Kleptocracy provides an answer, describing how Putin got to power, the cabal he brought with him, the billions they have looted, and his plan to restore the Greater Russia.

Russian scholar Dawisha describes and exposes the origins of Putin’s kleptocratic regime. She presents extensive new evidence about the Putin circle’s use of public positions for personal gain even before Putin became president in 2000. She documents the establishment of Bank Rossiya, now sanctioned by the US; the rise of the Ozero cooperative, founded by Putin and others who are now subject to visa bans and asset freezes; the links between Putin, Petromed, and “Putin’s Palace” near Sochi; and the role of security officials from Putin’s KGB days in Leningrad and Dresden, many of whom have maintained their contacts with Russian organized crime.

Putin’s Kleptocracy is the result of years of research into the KGB and the various Russian crime syndicates. Dawisha’s sources include Stasi archives; Russian insiders; investigative journalists in the US, Britain, Germany, Finland, France, and Italy; and Western officials who served in Moscow. Russian journalists wrote part of this story when the Russian media was still free. “Many of them died for this story, and their work has largely been scrubbed from the Internet, and even from Russian libraries,” Dawisha says. “But some of that work remains.”

Godfather of the Kremlin: The Decline of Russia in the Age of Gangster Capitalism

Paul Klebnikov

From nuclear superpower to impoverished nation, post-communist Russia has become one of the most corrupt regimes in the world. Paul Klebnikov pieces together the previous decade in Russian history, showing that a major piece of "the decline of Russia' puzzle lies in the meteoric business career of Boris Berezovsky.

Transforming himself from a research scientist to Russia's most successful dealmaker, Berezovsky managed to seize control of Russia's largest auto manufacturer, largest TV network, national airline, and one of the world's biggest oil companies. When Moscow's gangster families battled one another in the Great Mob War of 1993-1994, Berezovsky was in the thick of it. He was badly burned by a car bomb and his driver was decapitated. A year later, Berezovsky emerged as the prime suspect in the assassination of the director of the TV network he acquired. Although plagued by scandal, he enjoyed President Yeltsin's support, serving as the personal financial "advisor" to both Yeltsin and his family. In 1996, Berezovsky organized the financing of Yeltsin's re-election campaign-a campaign marred by fraud, embezzlement, and attempted murder. Berezovsky became the President's most trusted political advisor-playing a key role in forming governments and dismissing prime ministers.

Based on hundreds of taped interviews with top businessmen and government officials, secret police reports, contractual documents, and surveillance tapes, Godfather of the Kremlin is both a gripping story and a unique historical document.

Peter Pomerantsev

A journey into the glittering, surreal heart of 21st century Russia: into the lives of Hells Angels convinced they are messiahs, professional killers with the souls of artists, bohemian theatre directors turned Kremlin puppet-masters, supermodel sects, post-modern dictators and oligarch revolutionaries.

This is a world erupting with new money and new power, changing so fast it breaks all sense of reality, where life is seen as a whirling, glamorous masquerade where identities can be switched and all values are changeable. It is home to a new form of authoritarianism, far subtler than 20th century strains, and which is rapidly expanding to challenge the global order.

An extraordinary book - one which is as powerful and entertaining as it is troubling - Nothing is True and Everything is Possible offers a wild ride into this political and ethical vacuum

Peter Pomerantsev

When information is a weapon, everyone is at war.

We live in a world of influence operations run amok, a world of dark ads, psy-ops, hacks, bots, soft facts, ISIS, Putin, trolls, Trump. We've lost not only our sense of peace and democracy - but our sense of what those words even mean.

As Peter Pomerantsev seeks to make sense of the disinformation age, he meets Twitter revolutionaries and pop-up populists, 'behavioural change' salesmen, Jihadi fan-boys, Identitarians, truth cops, and much more. Forty years after his dissident parents were pursued by the KGB, he finds the Kremlin re-emerging as a great propaganda power. His research takes him back to Russia - but the answers he finds there are surprising.

Part reportage, part intellectual adventure, This is Not Propaganda is a Pynchon-like exploration of how we can reimagine our politics and ourselves in a time where truth has been turned topsy-turvy.

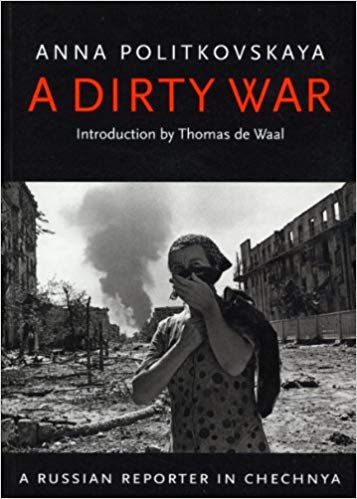

Anna Politkovskaya

An incisive study of a nation in chaos and its leader by a distinguished Russian journalist offers a detailed exposé of the rampant corruption in business, government, and the judiciary; severe problems within the military establishment; the ongoing war with Chechnya; and the role of Vladimir Putin in stifling civil liberties and the West for its support of the Russian leader.

Anna Politkovskaya

The Chechen War was supposed to be over in 1996 after the first Yeltsin campaign, but in the summer of 1999, the new Putin government decided, in their own words, to 'do the job properly'. Before all the bodies of those who had died in the first campaign had been located or identified, many more thousands would be slaughtered in another round of fighting.

The first account to be written by a Russian woman, A Dirty War is an edgy and intense study of a conflict that shows no sign of being resolved. Exasperated by the Russian government's attempt to manipulate media coverage of the war, journalist Anna Politkovskaya undertook to go to Chechnya, to make regular reports and keep events in the public eye.

In a series of despatches from July 1999 to January 2001 she vividly describes the atrocities and abuses of war, whether it be the corruption endemic in post-Communist Russia, in particular the government and the military, or the spurious arguments and abominable behaviour of the Chechen authorities. In these courageous reports, Politkovskaya excoriates male stupidity and brutality on both sides of the conflict and interviews the civilians whose homes and communities have been laid waste, leaving them nowhere to live, and nothing and no one to believe in.

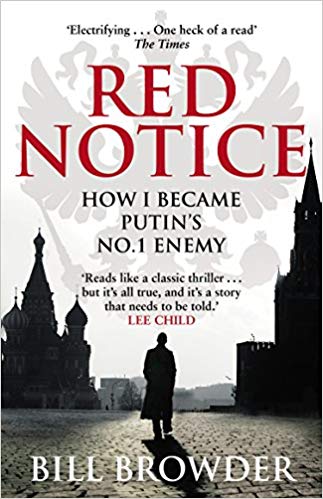

Bill Browder

In November 2009, the young lawyer Sergei Magnitsky was beaten to death by eight police officers in a freezing cell in a Moscow prison. His crime? Testifying against Russian officials who were involved in a conspiracy to steal $230 million of taxes.

Red Notice is a searing exposé of the whitewash of this imprisonment and murder. The killing hasn’t been investigated. It hasn’t been punished. Bill Browder is still campaigning for justice for his late lawyer and friend. This is his explosive journey from the heady world of finance in New York and London in the 1990s, through battles with ruthless oligarchs in turbulent post-Soviet Union Moscow, to the shadowy heart of the Kremlin.

With fraud, bribery, corruption and torture exposed at every turn, Red Notice is a shocking political roller-coaster.

ALEXANDER LITVINENKO

FSB defector, whistleblower and author

Alexander Litvinenko was a former officer of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and KGB, who fled from court prosecution in Russia and received political asylum in the United Kingdom.

As an officer of the Russian FSB secret service he specialised in tackling organized crime. According to US diplomats, Litvinenko coined the phrase Mafia state. In November 1998, Litvinenko and several other FSB officers publicly accused their superiors of ordering the assassination of the Russian tycoon and oligarch Boris Berezovsky. Litvinenko was arrested the following March on charges of exceeding the authority of his position. He was acquitted in November 1999 but re-arrested before the charges were again dismissed in 2000. He fled with his family to London and was granted asylum in the United Kingdom, where he worked as a journalist, writer and consultant for the British intelligence services.

During his time in London, Litvinenko wrote two books, Blowing Up Russia: Terror from Within and Lubyanka Criminal Group, wherein he accused the Russian secret services of staging the Russian apartment bombings and other terrorism acts in an effort to bring Vladimir Putin to power. He also accused Putin of ordering the murder in October 2006 of the Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya.

Russian intelligence

In 1991, Litvinenko was promoted to the Central Staff of the Federal Counterintelligence Service, specialising in counter-terrorist activities and infiltration of organised crime. He was awarded the title of "MUR veteran" for operations conducted with the Moscow criminal investigation department, the MUR. Litvinenko also saw active military service in many of the so-called "hot spots" of the former USSR and Russia. During the First Chechen War, Litvinenko planted several FSB agents in Chechnya. Although he was often called a "Russian spy" by western press, throughout his career he was not an 'intelligence agent' and did not deal with secrets beyond information on operations against organised criminal groups.

Litvinenko met Boris Berezovsky in 1994 when he took part in investigations into an assassination attempt on the oligarch. He later was responsible for the oligarch's security. Litvinenko's employment under Berezovsky and other security services created a conflict of interest, but such practice is usually tolerated by the Russian state.

In 1997, Litvinenko was promoted to the FSB Directorate of Analysis and Suppression of Criminal Groups, with the title of senior operational officer and deputy head of the Seventh Section

Conflict with FSB leadership

During his work in the FSB, Litvinenko discovered numerous connections between top brass of Russian law enforcement agencies and Russian mafia groups, such as the Solntsevo gang. He wrote a memorandum about this to Boris Yeltsin. Berezovsky arranged a meeting for him with FSB director Mikhail Barsukov and Deputy Director of Internal affairs Ovchinnikov to discuss the corruption problems; however, this had no effect. Litvinenko gradually realized that the entire system was corrupted from the top to the bottom. He explained: "If your partner bilked you, or a creditor did not pay, or a supplier did not deliver - where did you turn to complain? ...When force became a commodity, there was always demand for it. "Roofs" appeared, people who sheltered and protected your business. First it was provided by the mob, then by police, and soon even our own guys realized what was what, and then the rivalry began among gangsters, cops, and the Agency for market share. As the police and the FSB became more competitive, they squeezed the gangs out of the market. However, in many cases competition gave way to cooperation, and the services became gangsters themselves." According to US diplomats, Litvinenko coined the phrase Mafia state.

On 25 July 1998, Berezovsky introduced Litvinenko to Vladimir Putin. He said: "Go see Putin. Make yourself known. See what a great guy we have installed, with your help." On the same day, Vladimir Putin replaced Nikolay Kovalyov as the Director of the Federal Security Service, with help from Berezovsky. Litvinenko reported to Putin on corruption in the FSB, but Putin was unimpressed. Litvinenko said to his wife after the meeting: "I could see in his eyes that he hated me." Litvinenko said later that he was doing an investigation of Uzbek drug barons who received protection from the FSB, and Putin tried to stall the investigation to save his reputation.

On 13 November 1998, Berezovsky wrote an open letter to Putin in Kommersant. He accused senior officers of the Directorate of Analysis and Suppression of Criminal Groups Major-General Yevgeny Khokholkov, N. Stepanov, A. Kamyshnikov, and N. Yenin of ordering his assassination.

Four days later, on 17 November, Litvinenko and four other officers appeared together in a press conference at the Russian news agency Interfax. All officers worked for both FSB in the Directorate of Analysis and Suppression of Criminal Groups. They repeated the allegation made by Berezovsky. The officers also said they were ordered to kill Mikhail Trepashkin who was also present at the press conference, and to kidnap a brother of the businessman Umar Dzhabrailov. In 2007, Sergey Dorenko provided The Associated Press and The Wall Street Journal with a complete copy of an interview he conducted in April 1998 for ORT, a television station, with Litvinenko and his fellow employees. The interview, of which only excerpts were shown in 1998, shows the FSB officers, who were disguised in masks or dark glasses, claim that their bosses had ordered them to kill, kidnap or frame prominent Russian politicians and business people.

After holding the press conference, Litvinenko was dismissed from the FSB.[28] Later, in an interview with Yelena Tregubova, Putin said that he personally ordered the dismissal of Litvinenko, stating, "I fired Litvinenko and disbanded his unit ...because FSB officers should not stage press conferences. This is not their job. And they should not make internal scandals public.] Litvinenko also believed that Putin was behind his arrest. He said, "Putin had the power to decide whether to pass my file to the prosecutors or not. He always hated me. And there was a bonus for him: by throwing me to the wolves he distanced himself from Boris [Berezovsky] in the eyes of FSB's generals."

MI6

According to Litvinenko's widow, Marina Litvinenko, her husband cooperated with the British MI6 and MI5, working as a consultant and helping the agencies to combat Russian organised crime in Europe. During the public inquiry started in January 2015, it was confirmed that Litvinenko was recruited by MI6 to provide "useful information about senior Kremlin figures and their links with Russian organised crime", primarily related to Russian mafia activities in Spain.

Shortly before his death, Litvinenko tipped off Spanish authorities on several organised crime bosses with links to Spain. During a meeting in May 2006 he allegedly provided security officials with information on the locations, roles, and activities of several "Russian" mafia figures with ties to Spain, including Zahkar Kalashov, Izguilov and Tariel Oniani.

Litvinenko converted to Islam in Britain, Visitors to Litvinenko's deathbed included Boris Berezovsky and Litvinenko's father, Walter, who flew in from Moscow. Litvinenko told his father he had converted to Islam. Mrs Litvinenko said his father commented about it: "It doesn't matter. At least you're not a communist."

Mikhail Trepashkin said that in 2002 he had warned Litvinenko that an FSB unit was assigned to assassinate him. In spite of this, Litvinenko often travelled overseas with no security arrangements, and freely mingled with the Russian community in the United Kingdom, and often received journalists at his home.

Poisoning

On 1 November 2006, Litvinenko suddenly fell ill and was hospitalized. He died three weeks later, becoming the first confirmed victim of lethal polonium-210-induced acute radiation syndrome. Litvinenko's allegations about the misdeeds of the FSB and his public deathbed accusations that Russian president Vladimir Putin was behind his unusual malady resulted in worldwide media coverage.

Subsequent investigations by British authorities into the circumstances of Litvinenko's death led to serious diplomatic difficulties between the British and Russian governments. During the 2014–2015 trial, the Scotland Yard representative witnessed that "the evidence suggests that the only credible explanation is in one way or another the Russian state is involved in Litvinenko's murder". Another witness stated that Dmitry Kovtun had been speaking openly about the plan to kill Litvinenko that was intended to "set an example" as a punishment for a "traitor". The main suspect in the case, a former officer of the Russian Federal Protective Service (FSO), Andrey Lugovoy, remains in Russia.

BORIS NEMTSOV

Russian Politician

Nemtsov was shot and killed crossing the Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge near the Kremlin walking home after a meal out, in the company of Anna Duritskaya , a 23-year-old Ukrainian model who had been his girlfriend for two and a half years. She witnessed Nemtsov's killing, but was not physically harmed herself. TV Tsentr's video of the bridge at the time of the murder shows that it occurred as a municipal utility vehicle was passing by Nemtsov and a person is seen escaping from the scene in a white or grey automobile. According to the Russian newspaper Kommersant, at the time of the murder all the security cameras in the area were switched off for maintenance. The only video of the incident was obtained from the video feed camera of TV Tsentr studio, from a long distance. At the time of the killing, the camera was blocked by a stopped municipal vehicle. The killing happened the day before Nemtsov was due to lead the opposition march Vesna (Russian: весна, lit. 'spring'), a street demonstration organised to protest against economic conditions in Russia and against the war in Ukraine.

The killer was apparently waiting for Nemtsov on a side stairway leading to the bridge. At least six shots were fired, four of which hit Nemtsov; one wound was fatal. According to Kommersant sources, the killer used either a standard Makarov pistol or an IZh gas pistol modified for use with lethal ammunition.

Investigation

Russian President Vladimir Putin instructed the Investigative Committee, Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the Federal Security Service to create a single team to investigate the assassination of Nemtsov. The investigation team is headed by Igor Krasnov, who had previously investigated an attempt on the life of Anatoly Chubais and the murders of Stanislav Markelov and Anastasia Baburova.. The team is supervised by the head of the Investigative Committee in Moscow, general Alexander Drymanov. Drymanov has also supervised the investigation against Nadezhda Savchenko, the second trial against Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Platon Lebedev, as well as the charges of genocide during the Russo-Georgian War against Georgian military.

During the night following the assassination, Nemtsov's apartment on Malaya Ordynka street was searched and all documents and materials related to his business and political activities were confiscated.. Opposition media raised concerns this was done to retrieve a draft of report on Russian involvement in the war in Donbass announced by Nemtsov shortly before his death. Partial information on the report's contents were later revealed by Nemtsov's friends.

On 28 February, a white Lada Priora car possibly belonging to the assassin(s) was found abandoned. Russian state media reported that the car had a number-plate originating in the Republic of Ingushetia, although initial witnesses had stated that the white car involved in the shooting did not have any license plates. An underwater search in the Moscow River to retrieve the weapon presumably discarded by the killer after the assassination gave no result. A cash reward of 3 million rubles (~43,000 euros) is being offered for any information leading to the arrest and conviction of the killer.

Durytska, having testified before the investigative team, returned to Ukraine on 2 March. Because of reported threats to her life, the Prosecutor General of Ukraine Viktor Shokin provided Durytska with state protection.

By 3 March, the official investigation concluded that Nemtsov had been tracked from 11:00 am when he met Durytska in Sheremetyevo Airport. Nemtsov had been followed by three alternating cars en route from the airport to the city. On 23:22 the group of killers was ordered to move to the assigned spot, when Nemtsov and Durytska left the GUM café. On 23:29 the car with the assailant turned around under Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge and approached the stairs leading to the bridge. On 23:30 the assailant walked upstairs onto the bridge and moved towards Nemtsov and Durytska. Having walked past them, he turned around and fired at Nemtsov's back. After the assailant got into the car, it moved from the bridge to Bolotnaya Street, then to Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge, Mokhovaya Street and Tverskaya Street towards Okhotny Ryad and then turned to Bolshaya Dmitrovka before disappearing in local traffic. The car in which the assailant had escaped was later found and identified as grey ZAZ Chance. On 10 March Moskovskij Komsomolets published alleged CCTV photos of the suspects' vehicle, suggesting that they were following Nemtsov since September 2014, long before the Charlie Hebdo shooting.

Suspects

On 7 March 2015, the head of the Federal Security Service Alexander Bortnikov announced the arrest of two suspects, Anzor Gubashev and Zaur Dadaev (ru), both originating from the Northern Caucasus. According to Russian media, Zaur Dadaev had served in the Sever battalion of the Kadyrovtsy, while Anzor Gubashev had worked as a security guard for a Moscow hypermarket; according to other sources he is an employee of a private security firm. Both are from Ingushetia but for many years had been living outside the North Caucasus republic; they are related.They were formally charged on 8 March. Dadaev confessed to the crime; Gubashev denies any involvement. Three other persons were also detained as suspects, but not charged. All of them claimed they were innocent. According to Russian media another man blew himself up with a hand grenade in Grozny when police came to arrest him.

Zaur Dadaev, a former second-in-command to the leader of battalion Sever, Alibek Delimkhanov (the brother of Adam Delimkhanov and cousin of Ramzan Kadyrov), confessed that he had decided to kill Nemtsov because of his criticism of Islam and President of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov, according to Russian media.Dadaev apparently stated in his confession that his immediate manager during preparation of the murder was someone named Ruslik, who provided him with 5 million rubles, a ZAZ Chance car, and a gun. Investigators suspect that Ruslik is Ruslan Geremeev, the head of a battalion Sever unit Zaur Dadaev served in, a subordinate of Alimbek Delimkhanov and a nephew of Suleiman Geremeev, a member of Federation Council of Russia. After the murder, Ruslan Geremeev was under protection in the Chechen republic and later probably left Russia for United Arab Emirates or Turkey. In the end of April Ruslan Gereemev was officially assigned a status of a suspect.

Commenting on the events, President of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov said that he knew Dadaev as one of the bravest warriors who had fought in the Russian-Chechen Kadyrovtsy regiment since its creation. Dadaev had been awarded the Order of Courage, the Medal for Courage and further awards by the Chechen Republic. According to Kadyrov, Dadaev was deeply religious and greatly offended by Charlie Hebdo's publishing of the Muhammad cartoons and Nemtsov's support for the French cartoonists. However, the Kadyrovtsy were a secular unit fighting against radical Islamists and according to Dadaev's mother, her son had never mentioned Charlie Hebdo. Dadaev's mother also stated that her son was not a "strong believer" in Islam, and had in fact fought against Islamists ("Wahhabis") previously. Russia's opposition figures have called the theory that the murder was motivated by offense against Islam and the official line of inquiry by the Kremlin "more than absurd".

Russian media reported that Dadaev retracted his confession, explaining that he only confessed to avoid "what happened to Shavanov" – another suspect, who, according to the official version, blew himself up with a grenade during arrest attempt. A member of the Kremlin's advisory council on human rights, after visiting the suspects, said that Dadaev as well as the two other suspects, Anzor and Shagid Gubashev, most likely had been tortured while in detention.

Ironically, just before his murder, Nemtsov had stated, "The contract between Kadyrov and Putin—money in exchange for loyalty—is coming to an end. Where will Mr Kadyrov's 20,000 men go? What will they demand? How will they act? When will they come to Moscow?"

In late June 2017, five Chechen men were found guilty by a jury in a court at Moscow for agreeing to kill Nemtsov in exchange for 15 million rubles (US$253,000); neither the identity nor whereabouts of the person who hired them is known.

In July 2017 Zaur Dadaev was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment by a Russian court, while the other perpetrators were handed between 11 and 19 years each.

ANNA POLITKOVSKAYA

Journalist

Anna Politkovskaya's reporting from Chechnya that made her national and international reputation. For seven years she refused to give up reporting on the war despite numerous acts of intimidation and violence. Politkovskaya was arrested by Russian military forces in Chechnya and subjected to a mock execution. She was poisoned while flying from Moscow via Rostov-on-Don to help resolve the 2004 Beslan school hostage crisis, and had to turn back, requiring careful medical treatment in Moscow to restore her health.

Russian readers' main access to her investigations and publications was through Novaya Gazeta, a Russian newspaper known for its often-critical investigative coverage of Russian political and social affairs. From 2000 onwards, she received numerous international awards for her work. In 2004, she published Putin's Russia, a personal account of Russia for a Western readership.

Her post-1999 articles about conditions in Chechnya were turned into several award-winning books about Chechnya, life in Russia, and Russia under Vladimir Putin, including Putin's Russia.

Chechnya

Politkovskaya won a number of awards for her work.She used each of these occasions to urge greater concern and responsibility by Western governments that, after the 11 September attacks on the United States, welcomed Putin's contribution to their "War on Terror". She talked to officials, the military and the police and also frequently visited hospitals and refugee camps in Chechnya and in neighbouring Ingushetia to interview those injured and uprooted by the renewed fighting.

In numerous articles critical of the war in Chechnya and the pro-Russian regime there, Politkovskaya described alleged abuses committed by Russian military forces, Chechen rebels, and the Russian-backed administration led by Akhmad Kadyrov and his son Ramzan Kadyrov. She also chronicled human rights abuses and policy failures elsewhere in the North Caucasus. In one characteristic instance in 1999, she not only wrote about the plight of an ethnically-mixed old peoples' home under bombardment in Grozny, but helped to secure the safe evacuation of its elderly inhabitants with the aid of her newspaper and public support. Her articles, many of which form the basis of A Dirty War (2001) and A Small Corner of Hell (2003), depict a conflict that brutalised both Chechen fighters and conscript soldiers in the federal army, and created hell for the civilians caught between them.

As Politkovskaya reported, the order supposedly restored under the Kadyrovs became a regime of endemic torture, abduction, and murder, by either the new Chechen authorities or the various federal forces based in Chechnya. One of her last investigations was into the alleged mass poisoning of Chechen schoolchildren by a strong and unknown chemical substance which incapacitated them for many months.

Poisoning

While flying south in September 2004 to help negotiate with those who had taken over a thousand hostages in a school in Beslan (North Ossetia), Politkovskaya fell violently ill and lost consciousness after drinking tea given to her by an Aeroflot flight attendant. She had reportedly been poisoned, with some accusing the former Soviet secret police poison facility.

Threats from OMON officer

In 2001, Politkovskaya fled to Vienna, following e-mail threats that a police officer whom she had accused of atrocities against civilians in Chechnya was looking to take revenge. Corporal Sergei Lapin was arrested and charged in 2002, but the case against him was closed the following year. In 2005, Lapin was convicted and jailed for the torture and subsequent disappearance of a Chechen civilian detainee, the case exposed by Politkovskaya in her article "Disappearing People"

A former fellow officer of Lapin's was among the suspects in Politkovskaya's murder, on the theory that the motive might have been revenge for her part in Lapin's conviction.

Conflict with Ramzan Kadyrov

In 2004, Politkovskaya had a conversation with Ramzan Kadyrov, then Prime Minister of Chechnya. One of his assistants said to her, "Someone ought to have shot you back in Moscow, right on the street, like they do in your Moscow". Ramzan repeated after him: "You're an enemy. To be shot...." On the day of her murder, said Novaya Gazeta's chief editor Dmitry Muratov, Politkovskaya had planned to file a lengthy story on the torture practices believed to be used by the Chechen security detachments known as Kadyrovites. In her final interview, she described Kadyrov—now president of Chechnya—as the "Chechen Stalin of our days"

Criticism of Vladimir Putin and FSB

After Politkovskaya became widely known in the West, she was commissioned to write Putin's Russia (later subtitled Life in a Failing Democracy), a broader account of her views and experiences after former KGB lieutenant colonel Vladimir Putin became Boris Yeltsin's Prime Minister, and then succeeded him as President of Russia. This included Putin's pursuit of the Second Chechen War. In the book, she accused the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) of stifling all civil liberties in order to establish a Soviet-style dictatorship, but admitted:

[It] is we who are responsible for Putin's policies ... [s]ociety has shown limitless apathy ... [a]s the Chekists have become entrenched in power, we have let them see our fear, and thereby have only intensified their urge to treat us like cattle. The KGB respects only the strong. The weak it devours. We of all people ought to know that.

She also wrote:

We are hurtling back into a Soviet abyss, into an information vacuum that spells death from our own ignorance. All we have left is the internet, where information is still freely available. For the rest, if you want to go on working as a journalist, it's total servility to Putin. Otherwise, it can be death, the bullet, poison, or trial—whatever our special services, Putin's guard dogs, see fit.

"People often tell me that I am a pessimist, that I don't believe in the strength of the Russian people, that I am obsessive in my opposition to Putin and see nothing beyond that", she opens an essay titled "Am I Afraid?", finishing it—and the book—with the words "If anybody thinks they can take comfort from the 'optimistic' forecast, let them do so. It is certainly the easier way, but it is the death sentence for our grandchildren."

Attempted hostage negotiations

Politkovskaya was closely involved in attempts to negotiate the release of hostages in the Moscow theatre hostage crisis of 2002. When the Beslan school hostage crisis erupted in the North Caucasus in early September 2004, Politkovskaya attempted to fly there to act as a mediator, but was taken off the plane, acutely ill due to an attempted poisoning, in Rostov-on-Don (see Poisoning).

Access to Russian authorities

In Moscow, Politkovskaya was not invited to press conferences or gatherings that Kremlin officials might attend, in case the organisers were suspected of harbouring sympathies toward her. Despite this, many top officials allegedly talked to her when she was writing articles or conducting investigations. According to one of her articles, they did talk to her, "but only when they weren't likely to be observed: outside in crowds, or in houses that they approached by different routes, like spies". She also claimed that the Kremlin tried to block her access to information and discredit her:

I will not go into the other joys of the path I have chosen, the poisoning, the arrests, the threats in letters and over the Internet, the telephoned death threats, the weekly summons to the prosecutor general's office to sign statements about practically every article I write (the first question being, "How and where did you obtain this information?"). Of course I don't like the constant derisive articles about me that appear in other newspapers and on Internet sites presenting me as the madwoman of Moscow. I find it disgusting to live this way. I would like a bit more understanding.

Death threats

After Politkovskaya's murder, Vyacheslav Izmailov, her colleague at Novaya Gazeta—a military man who had helped negotiate the release of dozens of hostages in Chechnya before 1999—said that he knew of at least nine previous occasions when Politkovskaya had faced death, commenting "Frontline soldiers do not usually go into battle so often and survive".

Politkovskaya herself did not deny being afraid, but felt responsible and concerned for her informants. While attending a December 2005 conference on the freedom of the press in Vienna organised by Reporters Without Borders, she said "People sometimes pay with their lives for saying aloud what they think. In fact, one can even get killed for giving me information. I am not the only one in danger. I have examples that prove it." She often received death threats as a result of her work, including being threatened with rape and experiencing a mock execution after being arrested by the military in Chechnya.

Assassination

On 7 October 2006, she was murdered in the elevator of her block of flats, an assassination that attracted international attention. In June 2014, five men were sentenced to prison for the murder, but it is still unclear who ordered or paid for the contract killing.

A Russian Diary

In May 2007, Random House posthumously published Politkovskaya's A Russian Diary, containing extracts from her notebook and other writings. Subtitled A Journalist's Final Account of Life, Corruption, and Death in Putin's Russia, the book gives her account of the period from December 2003 to August 2005, including what she described as "the death of Russian parliamentary democracy", the Beslan school hostage crisis, and the "winter and summer of discontent" from January to August 2005. Because she was murdered "while translation was being completed, final editing had to go ahead without her help", wrote translator Arch Tait in a note to the book.

"Who killed Anna and who lay beyond her killer remains unknown", wrote Jon Snow, the main news anchor for the United Kingdom's Channel 4 in his foreword to the book's UK edition. "Her murder robbed too many of us of absolutely vital sources of information and contact", he concluded, "Yet it may, ultimately, be seen to have at least helped prepare the way for the unmasking of the dark forces at the heart of Russia's current being. I must confess that I finished reading A Russian Diary feeling that it should be taken up and dropped from the air in vast quantities throughout the length and breadth of Mother Russia, for all her people to read."

ARTYOM BOROVIK

Journalist

Borovik was a prominent Russian journalist and media magnate who specialised in investigative exposés of the Kremlin. He was killed in a mystery air crash at Moscow airport.

Borovik was one of the loudest critics in Moscow of the acting president, Vladimir Putin, and of Mr Putin's war against Chechnya.

Borovik first appeared on Soviet television in late 1980s as one of the hosts of a highly progressive and successful Vzglyad (which literally translates as The View or The Look), a kind of satirical television show watched weekly by as many as 100 million people.

Borovik was a pioneer of investigative journalism in the Soviet Union during the beginning of glasnost. He worked for the American CBS program 60 Minutes during the 1990s, and began publishing his own monthly investigative newspaper Top Secret, which grew into a mass-media company involved in book publishing and television production. In 1999, Borovik started an investigative program called Versia in partnership with U.S. News & World Report.

His Top Secret TV programme often focused on corruption cases involving Russia's political and economic elite. The programme, as well as Borovik's print publications, Top Secret and Versia, were openly critical of Vladimir Putin. Borovik also opposed the First and Second Chechen Wars. His last investigation was about the Russian apartment bombings of 1999, which he and others alleged had actually been orchestrated by the Russian FSB. In one of his last papers he quoted Vladimir Putin who said: "There are three ways to influence people: blackmail, vodka, and the threat to kill." This quote Borovik based on Der Spiegel and Stern, German magazines.

The apartment bombings were used as a pretext for the launch of the Second Chechen War which Borovik investigated extensively, even exposing Russian atrocities. The front page of one of Borovik's newspaper, Versiya on the week of his death was headlined "The Routine Genocide" in reference to alleged atrocities perpetrated in Chechnya by Russian troops. That was highly unusually for the generally compliant Russian media.

Mr Borovik's newspapers, Top Secret and Versiya, concentrated on juicy revelations of the venality and the corruption among Russia's rich and powerful. In recent months, the Borovik publications have been bitterly critical of Mr Putin, his erstwhile KGB connections, and his closeness to the entourage of the former president Boris Yeltsin.

Death speculation

According to historian Yuri Felshtinsky and political scientist Vladimir Pribylovsky, Borovik's death may be linked to his publications about Vladimir Putin just before the presidential elections that took place on 26 March. He died three days prior to the scheduled publication of materials about Putin's childhood. Borovik had studied Vera Putina's claims that Putin is her son. Putin himself claims his parents had passed away.

One of the silent aspects of the Chechen conflict is said to be the expansion of the Oligarchy's mafia state into the region to seize control of valuable natural resources. The Yakovlev Yak-40 was chartered by the Chechen oil industry executive Ziya Bazhayev, who heads the Alliance Group oil company, for a flight to Kiev. It is likely Bazhayev could have been a target of business rivals.

Bazayev worked in the oil industry in Grozny, the Chechen capital which has been destroyed by Russian bombardment and is occupied by Russian troops.

"It's very difficult these days for a Chechen to be in the oil industry in Russia," said the former Russian prime minister Sergei Kiriyenko, fuelling speculation about foul play.

Commentators surmised that enemies of the oil executive in Russia's notoriously ruthless business mafias were responsible for the deaths, or enemies of Borovik whose newspapers and television shows crusaded against corruption in Russia's political and economic elites.

"Power in Russia is not in the hands of the democrats or the communists, it's in the hands of organised crime and the mafia," Borovik once famously declared

'Official' story

The official investigation into the crash by the Interstate Aviation Committee revealed that whilst snow was removed from the aircraft exterior, de-icing fluid was not applied. The crew did not ask for permission to enter the taxiway, which was done at too high a speed for the icy conditions, and the flaps were set to 11°, instead of 20°. The aircraft reached a speed of 165 km/h, when the crew began to rotate the aircraft, at which stage it reached a 13° angle of attack, and stalled 8–10 metres off the ground, and reached a height of 63 metres, before crashing.

It is also claimed that Borovik's originally scheduled aircraft was due to depart at 8:00 in the morning of 9 March 2000; however, due to Borovik's planned flight being delayed, Bazhayev offered Borovik a seat on his Yakovlev Yak-40 flight

Problems with the 'official' story

The three-engined passenger jet is generally regarded as a reliable aircraft. The plane that crashed yesterday had been in use for 24 years.

Pilots at Sheremetevo told Russian television that even if all three engines had failed on takeoff, the plane would still have been able to land relatively safely.

"I don't think oil magnates use unreliable aircraft," said Vsevolod Bogdanov, head of the Russian journalists' union.

PAUL KLEBNIKOV

Journalist

Paul Klebnikov (August 6, 1964 – July 9, 2004) was an American journalist and historian of Russian history. He worked for Forbes magazine for more than 10 years and at the time of his death was chief editor of the Russian edition of Forbes. His murder in Moscow in 2004 was seen as a blow against investigative journalism in Russia. Three Chechens accused of taking part in the murder were acquitted. Though the murder appeared to be the work of assassins for hire, as of 2018, the organizers of the murder had yet to be identified.

Paul Klebnikov was born in New York to a family of Russian émigrés with a long military and political tradition: his great-great-great-grandfather Ivan Puschin participated in the Decembrist revolt in 1825 and was exiled to Siberia, and his great-grandfather, an admiral in the White Russian fleet, was assassinated by Bolsheviks.

Klebnikov pursued a PhD at the London School of Economics, where he would go on to win the Leonard Schapiro Prize "for excellence in Russian studies". He wrote his doctoral thesis on agrarian reform in Russia following the Stolypin Reforms that sought to build an independent, progressive, and prosperous peasantry. From 1987–88, he lectured at the Institute of European Studies in London..

On September 22, 1991, he married Helen "Musa" Train, the daughter of prominent Wall Street banker John Train. The couple would go on to have three children.

Reporting On Russia

Klebnikov joined the Forbes in 1989 and gained a reputation for investigating murky post-Soviet business dealings and corruption. In 1996, he wrote a cover story for Forbes titled "Godfather of the Kremlin?" with the kicker 'Power. Politics. Murder. Boris Berezovsky could teach the guys in Sicily a thing or two.', comparing Russian tycoon Boris Berezovsky to the Sicilian mafia. The article was published without a byline, but was widely known to be Klebnikov's work. Klebnikov soon received death threats, and took a break from reporting in Russia to live with his family in Paris.

Berezovsky subsequently sued Forbes for libel in a British court. Because the story had been published in an American magazine about a Russian citizen, the choice of venue was described by several authorities as libel tourism. Berezovsky won a partial retraction of the story in 2003.

Meanwhile, Klebnikov expanded the article into the 2000 book Godfather of the Kremlin: Boris Berezovsky and the Looting of Russia. Believed to be based heavily on interviews with Alexander Korzhakov, the head of security for former president Boris Yeltsin, the book described the privatization process used by Yeltsin as "the robbery of the century" and detailed the alleged corruption of various Russian businesspeople, particularly focusing on Berezovsky. The book met with mixed reviews in journalistic circles. A New York Times reviewer praised it as "richly detailed" and "effectively angry".

Klebnikov released a second book, Conversation with a Barbarian: Interviews with a Chechen Field Commander on Banditry and Islam, in 2003. The book is a transcript of a lengthy interview with Chechen rebel leader Khozh-Ahmed Noukhayev, conducted in Baku, Azerbaijan. In the course of the interview, Nukhayev gives his views on Islam and Chechen society.

In the same year, Klebnikov was chosen to be the first editor of the Russian edition of Forbes. Because his wife and children did not wish to move to Russia, Klebnikov agreed with them that he would take the post for only one year. The magazine only put out four issues before his death, including an article covering Russia's 100 wealthiest individuals, which some commentators speculate may have been the reason for his death.

Murder

On July 9, 2004, while leaving the Forbes office, Klebnikov was attacked on a Moscow street late at night by unknown assailants who fired at him from a slowly moving car. Klebnikov was shot four times and initially survived, but he died at the hospital after being transported in an ambulance that had no oxygen bottle and the hospital elevator that was taking him to the operating room broke down.

Russian 'investigation'

In 2006, prosecutors accused Chechen rebel leader Khozh-Ahmed Noukhayev, subject of Klebnikov's book A Conversation with a Barbarian, of masterminding the attack. Three Chechen men—Kazbek Dukuzov, Musa Vakhayev, and Fail Sadretdinov—were arrested and tried in a closed trial for the murder, but all three were acquitted. Sadretdinov was later convicted on unrelated charges and sentenced to nine years' imprisonment, while Vakhayev and Dukuzov had their acquittals overturned by the Supreme Court of Russia, allowing them to be re-prosecuted.

In July 2007, on the third anniversary of the murder, the U.S. Department of State protested the continuing failure of the Russian government to find the perpetrators, calling for further investigation.[21] U.S. President George W. Bush also appealed directly to Russian President Vladimir Putin for action.

Vakhayev and Dukuzov were scheduled to be retried in 2007, again in a closed trial, but could not be located. On December 17, the trial was postponed again because of Dukuzov's continued absence. The process then "quietly stalled".

In July 2009, Russian authorities agreed to reopen the suspended investigation into the killings. They also stated that they no longer believed Nukhayev had masterminded the murder (though they continued to believe he played some role in the attack).

SERGEI MAGNITSKY

Corruption Whistleblower

Sergei Leonidovich Magnitsky (8 April 1972 – 16 November 2009) was a Russian tax advisor. His arrest in 2008 and subsequent death after eleven months in police custody generated international media attention and triggered both official and unofficial inquiries into allegations of fraud, theft and human rights violations in Russia.

Magnitsky alleged there had been large-scale theft from the Russian state, sanctioned and carried out by Russian officials.[citation needed] He was arrested and eventually died in prison seven days before the expiration of the one-year term during which he could be legally held without trial. In total, Magnitsky served 358 days in Moscow's Butyrka prison. He developed gall stones, pancreatitis, and a blocked gall bladder, and received inadequate medical care. A human rights council set up by the Kremlin found that he had been physically assaulted shortly before his death. His case has become an international cause célèbre.

The United States Congress and President Barack Obama enacted the Magnitsky Act at the end of 2012, barring those Russian officials believed to be involved in Magnitsky's death from entering the United States or using its banking system. In response, Russia condemned the Act and claimed Magnitsky was guilty of crimes.

In early January 2013, the Financial Times wrote that "the Magnitsky case is egregious, well documented and encapsulates the darker side of Putinism

Background

Magnitsky was an auditor at the Moscow law firm Firestone Duncan, working for its owner, Jamison Firestone.

Over the years of its operation Hermitage had, on a number of occasions, supplied to the press information related to corporate and governmental misconduct and corruption within state-owned Russian enterprises. Hermitage's company co-founder, American Bill Browder, was expelled from Russia in 2005 as a national threat. Browder has said that he represented a threat only "to corrupt politicians and bureaucrats" in Russia, and believed that the ouster was conducted in order to leave his company open for exploitation. In November 2005, Browder had arrived in Moscow to be told his visa had been annulled. He was deported the next day and has not seen his Moscow home since.

On 4 June 2007, Hermitage's Moscow office was raided by about 20 Ministry of Interior officers. The offices of Firestone Duncan were also raided. The officers had a search warrant alleging that Kamaya, a company administered by Hermitage, had underpaid its taxes. This was highly irregular, as the Russian tax authorities had just confirmed in writing that this company had overpaid its tax. In both cases, the search warrants permitted the seizure of materials related only to Kamaya. But, in both cases the officers illegally seized all the corporate, tax documents and seals for any company that had paid a large amount of Russian taxes, including documents and seals for many of Hermitage's Russian companies.. In October 2007, Browder received word that one of the firms maintained in Moscow had a judgment against it for an alleged unpaid debt of hundreds of millions of dollars. According to Browder, this was the first he had heard of this court case and he did not know the lawyers who represented his company in court. Magnitsky was assigned to investigate the case.

Exposing the scandal

In his investigation, auditor Magnitsky came to believe that the police had given the materials taken during the police raids to organized criminals, who used them to take over three of Hermitage's Russian companies and who fraudulently reclaimed $230m (£140m) of the taxes previously paid by Hermitage. He also claimed police had accused Hermitage of tax evasion solely to justify the police raids, so they could take the materials needed to hijack the Hermitage companies and effect the tax refund fraud. Magnitsky's testimony implicated police, the judiciary, tax officials, bankers, and the Russian mafia. In spite of the initial dismissal of his claims, Magnitsky's core allegation that Hermitage had not committed fraud—but had been victimized by it—was eventually validated. A sawmill foreman pleaded guilty in the matter to "fraud by prior collusion", though the foreman would maintain that police were not part of the plan. Before then, however, Magnitsky became the subject of investigation by one of the policemen against whom he had testified as involved in the fraud. According to Browder, Magnitsky was "the 'go-to guy' in Moscow on courts, taxes, fines, anything to do with civil law."

According to Magnitsky's investigation, the documents that had been taken by the Russian police in June 2007 were used to forge a change in ownership of Hermitage.[8] The thieves used the forged contracts to claim Hermitage owed $1 billion to shell companies. Unbeknownst to Hermitage, those claims were later authenticated by judges. In every instance, lawyers hired by the thieves to represent Hermitage (unbeknownst to Hermitage) pleaded guilty on the company's behalf and agreed to the claims, thereby obtaining judgments for debts that did not exist; all while Hermitage officials were unaware of these court proceedings.

The new owner, based in Tatarstan, turned out to be Viktor Markelov, a convicted murderer released two years into his sentence.[8] The company's fake debt was used to make the companies look unprofitable in order to justify a refund of $230 million in tax that the companies had paid when they had been under Hermitage's control. The refund was issued Christmas Eve of 2007. It was the largest tax rebate in Russian history.

Hermitage contacted the Russian government with the findings of its investigation. The money, which was not Hermitage's, belonged to the Russian people. Rather than opening a case against the police and the thieves, the Russian authorities opened a criminal case against Magnitsky.

Magnitsky was arrested and imprisoned at the Butyrka prison in Moscow in November 2008 after being accused of colluding with Hermitage.. Held for 11 months without trial, he was, as reported by The Telegraph, "denied visits from his family" and "forced into increasingly squalid cells." He developed gall stones, pancreatitis and calculous cholecystitis, for which he was given inadequate medical treatment during his incarceration. Surgery was ordered in June, but never performed; detention center chief Ivan P. Prokopenko later said that he "...did not consider Magnitsky sick... Prisoners often try to pass themselves off as sick, in order to get better conditions."

On 16 November 2009, eight days before he would have had to be released if he were not brought to trial, Magnitsky died. Prison officials at first attributed his death to a "rupture to the abdominal membrane" and later to a heart attack. Reporters learned that Magnitsky had complained of worsening stomach pain for five days prior to his death and that by the 15th, he was vomiting every three hours, and had a visibly swollen stomach. On the day of his death, the prison physician, believing Magnitsky had a chronic disease, sent him by ambulance to and later transferred him to Matrosskaya Tishina prison's medical unit, which was equipped to help him.[16] But the surgeon there—who described Magnitsky as "agitated, trying to hide behind a bag and saying people were trying to kill him"—prescribed only a painkiller, and left him to receive a psychiatric evaluation. Magnitsky was found dead in his cell a little over two hours later.

According to Ludmila Alekseeva, leader of the Moscow Helsinki Group, Magnitsky had died from being beaten and tortured by several officers of the Russian Ministry of Interior. The official death certificate stated "closed cerebral cranial injury" as the cause of death (in addition to the other conditions mentioned above), and the post-mortem examination showed numerous bruises and wounds on Magnitsky's legs and hands. Another post-mortem from 2011 summarized the death as being caused by "traumatic application of the blunt hard object (objects)" as confirmed by "abrasions, ecchymomas, blood effusions into the soft tissues".

Journalist Owen Matthews described Magnitsky's suffering in Moscow's Butyrka prison:

According to [Magnitsky's] heartbreaking prison diary, investigators repeatedly tried to persuade him to give testimony against Hermitage and drop the accusations against the police and tax authorities. When Magnitsky refused, he was moved to more and more horrible sections of the prison, and ultimately denied the medical treatment which could have saved his life.

Aftermath and official investigations

According to Russian news agency RIA Novosti, Magnitsky's death "caused public outrage and sparked discussion of the need to improve prison healthcare and to reduce the number of inmates awaiting trial in detention prisons."

An independent investigatory body, the Moscow Public Oversight Commission, indicated in December 2009 that "psychological and physical pressure was exerted upon" Magnitsky. One of the Commissioners said that while she had first believed his death was due to medical negligence, she had developed "the frightening feeling that it was not negligence but that it was, to some extent, as terrible as it is to say, a premeditated murder."

An official investigation was ordered in November 2009 by Russian president Dmitry Medvedev. Russian authorities had not concluded their own investigation as of December 2009, but 20 senior prison officials had already been fired as a result of the case. In December 2009, in two separate decrees, Medvedev fired Alexander Piskunov, deputy head of the Federal Penitentiary Service, and signed a law forbidding the jailing of individuals who are suspected of tax crimes. Magnitsky's death is also believed to be linked to the firing of Major-General Anatoli Mikhalkin, formerly the head of the Moscow division of the tax crimes department of the Interior Ministry. Mikhalkin was among those accused by Magnitsky of taking part in fraud.

In 2016 a large criminal investigation was completed in Russia where a number of public officers from tax, security, and customs agencies were involved in large scale VAT carousel fraud schemes, very similar to the one that was used in the fraud against Hermitage Capital, and with the same high-ranking officers providing krysha (Russian: Крыша, "protection") in both cases. A few low-ranking officers were convicted in the case, but no mid- or high-ranking officers were even indicted, despite total losses to the budget exceeding 20 billion rubles. Since worsening of relations with the European Union after 2014, the version officially promoted in Russia is that Bill Browder's Hermitage Capital was responsible for tax fraud and that Magnitsky died as result of his conspiracy involving Alexey Navalny, which was highlighted in a 2016 "investigative" film by Andrei Nekrasov. Both Magnitsky's wife and mother, whose manipulated citations were used in the film, wrote a protest letter criticizing the film for bias and manipulations.

On 21 March 2017, the Magnitsky family's lawyer, Nikolai Gorokhov fell, or was thrown, from the 4th floor of his apartment building in Moscow. Seriously injured, he was taken to hospital by helicopter.

IGOR DOMNIKOV

Journalist

Igor Domnikov (May 29, 1959 – July 16, 2000) was a Russian journalist and editor for special topics involving business corruption for Novaya Gazeta in Moscow, Russia, who was murdered in 2000. Although some individuals were convicted of the attack in 2007, the suspected mastermind, Sergey Dorovsky, an ex-government official from Lipetsk Region, was never convicted as the statute of limitations on the case had expired.

Death

Domnikov was attacked outside of his Moscow apartment by several men wielding hammers. Domnikov was hit on the head repeatedly, which knocked him unconscious. Due to the injuries sustained in the initial beating, Igor was sent to the Burdenko Institute, where he remained in a coma until his death two months later.

When Pavel Sopot was accused of masterminding the murder he stated: "I had no motive to mastermind the attack; I regret what happened, but I'm a small and modest entrepreneur who happened to be close to that story because of my naivety." Sopot was however in regular contact with Dorovsky in the days leading up to the crime.

A push for justice led to arrests and convictions in August 2007. Five members of a criminal gang were convicted of murdering Domnikov. They were sentenced to prison terms varying from 18 years to life for the Domnikov slaying and numerous other crimes.

Ten years after the attack, on March 11, 2015, Dorovsky was charged with the murder of Domnikov. Dorovsky was charged with "solicitation of deliberate infliction of grievous bodily harm to a victim due to his/her professional activity." This brought attention to the already popular paper in Russia but also brought unwanted attention and more attacks. The case, however, was not successfully prosecuted as the statute of limitations had run out.

Impact

The impact of the murder of Domnikov has been felt all across Russia and especially in the media culture. More people are being prosecuted in Russia for harassing and assaulting journalists.

Domnikov was just one in a line of murdered journalists from the Novaya Gazeta. After the murder of reporters such as Stanislav Markelov, Anastasia Baburova, Anna Politkovskaya, Yuri Shchekochikhin and Domnikov, Novaya Gazeta has talked about supplying their reporters and lawyers with guns to protect themselves. The murders of reporters working for the Novaya Gazeta are a large blow to Russia because they are the only critical newspaper in Russia according to Dmitry Muratov.

Reactions

Koïchiro Matsuura, director general of UNESCO, said, "Violent acts against journalists are attacks on freedom of expression and violations of the right - enshrined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights - to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media."

Joel Simon, the executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, said, "Justice has been served in a journalist murder for the first time since President Vladimir Putin took office in 2000."

The director of the Center for Journalism in Extreme Situations said, "I'm afraid Domnikov's might become another in a long line of unsolved journalist murder cases."

The Novaya Gazeta displays a photograph in honor of the late Igor Domnikov in a case in the lobby of their main building in Moscow. Sokolov, a former colleague of Domnikov, said "it was all a tragic mistake," in reference to the beating and murder of the journalist. Many of Domnikov's colleagues seem to believe the murder of a result of mistaken identity. "We think that Igor Domnikov was mistaken for Oleg Sultanov," stated the late friend and coworker Yuri Shchekochikhin

ISKANDAR KHATLONI

Journalist

Iskandar Khatloni (October 1954 – September 21, 2000) was a journalist from Tajikistan who worked for Radio Free Europe and was murdered in Moscow, Russia while covering the Second Chechen War.

In the 1980s at the onset of glasnost in the Soviet Union Khatloni began worked as a BBC correspondent. In 1996 he became a correspondent for the Tajik language division of the Prague-based Radio Free Europe. In addition to his journalistic work, Khatloni was a distinguished poet and had published four volumes of verse.

Before his death Khatloni had been assigned to Moscow to report on human rights abuses in Chechnya.

Murder

On the evening of 22 September 2000 Khatloni was attacked inside of his Moscow apartment by an unknown, axe-wielding assailant. Khatloni was struck twice in the head and then stumbled onto the street and collapsed. He was later found by a passerby and taken to Moscow's Botkin Hospital, where he died that night of a serious head wound.

Speculation surrounding Khatloni's murder has focused on his coverage of the war in Chechnya, a politically sensitive topic that brought great peril to Russian-based journalists covering the subject. Just the previous spring, Igor Domnikov of Novaya Gazeta had been murdered while covering abuses by the Russian armed forces in Chechnya. Radio Free Europe's coverage of the Chechen conflict had caused the Russian Media Ministry to declare earlier in the year that the independent radio station was "hostile to our state." Moscow police opened an investigation of Khatloni's murder, but no arrests were ever made in the case.

Khatloni was survived by his wife Kimmat and a daughter from a previous marriage. He was buried in his native Tajikistan.

MAGOMED YEVLOYEV

Journalist, Lawyer and Businessman

Yevloyev was the owner of the news website Ingushetiya.ru, known for being highly critical of Murat Zyazikov, the President of Ingushetia, a federal subject of Russia locating in the North Caucasus region.

In July 2007, the public procurator of Moscow's Kuntsevo municipality initiated a criminal case accusing Yevloyev of "inciting inter-ethnic hatred", though in the end Yevloyev was never indicted for any criminal activities. In October 2007, the Tsechoyev murder case was reopened and Yevloyev's family house in Malgobek was searched. After the search, Yevloyev's father, Yakhyu Yevloyev, convinced his son to publicly sever all ties with the Ingushetia.ru site, as it appeared to be too dangerous.

Yevloyev did not, however, completely withdraw from the politics of Ingushetia. He was one of the organizers of the I did not vote campaign, intended to expose mass voter fraud in Ingushetia during the 2008 Russian presidential election. According to official data, 98% of eligible Ingushetia voters took part in the elections, almost all voting for Dmitry Medvedev. But Yevloyev alleged that less than half of registered voters had actually participated in the elections, and therefore sought to compile a list of people who could personally guarantee that they did not vote in the election. If the list proved to include more than 2% of Ingushetia's voting registry, it might constitute proof of massive election fraud.

Yevloyev also organized and financed a campaign collecting signatures calling for the removal of Ingushetia President Zyazikov, and the restoration of the previous Ingushetia president Ruslan Aushev.

In the beginning of 2008, the office of the Ingushetia public procurator initiated hearings in Kuntsevo Court, demanding that access to the site Ingushetia.ru be restricted. According to the prosecutors, in an interview with Ingushetia businessman Musa Keligov hosted on the site, Keligov directly accused Zyazikov of connections with guerillas. The prosecutors argued that this material constituted libel as well as "public advocacy of extremist activity". In May 2008, the court issued an injunction demanding that Russian providers "limit access to the site by filtering its IP addresses". In June 2008, the court characterized the site as "extremist" and demanded its closure. The site was not closed. According to Ingushetia.ru's lawyer Kaloy Akhilgov, since the site is registered in the United States, it is therefore outside the jurisdiction of Russian courts. Akhilgov also stated that the decision is technically incorrect because it classifies the site under the heading "mass media" despite the fact that the site is not officially registered as such. Akhilgov added that they intended to appeal the court decision.

Murder

On 31 August 2008, Magomed Yevloyev was shot in the temple and killed while in police custody. Weeks before his killing, it was rumoured that Magomed knew his life was in danger and he had planned on seeking political asylum in a European Union country. Local police claimed that Yevloyev was shot after he had attempted to grab an assault rifle from one of the police officers in the car. Human rights groups have rejected this account of Yevloyev's death, and the United States State Department has called for an investigation of the killing and for those responsible to be "held to account for what happened". A spokesman for Vladimir Putin has said that an investigation will take place, but that Yevloyev had resisted arrest.

In July 2008, Human Rights Watch documented dozens of arbitrary detentions, disappearances, acts of torture, and extrajudicial executions in Ingushetia.

The Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe denounced Yevloyev's killing as an "assassination" aimed at cracking down on dissent in Ingushetia. The killing also triggered calls for Ingushetia's independence from Russia. The organizer of the protest rally, Magomed Khazibiyev, declared that the Ingush opposition would demand independence, appealing to Russia's recognition of Georgia's breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia as precedent.

The funeral of Yevloyev developed into an anti-government protest, in which, according to organizers, several thousands participated. Early on 2 September, police dispersed a sleeping crowd of around 50 men who remained in the main square in Nazran, Ingushetia's capital city.

His death investigation case is classified as "Murder by negligence" according to the Criminal Code of Russia. Another criminal case for his illegal detention (according to the investigators, police did not have the right to arrest him when they did) was opened in February 2009, but withdrawn in March 2009.

Court

On 11 December 2009, a court in Ingushetia found Ibragim Yevloyev guilty of unintentionally murdering Magomed Yevloyev. Ibragim Yevloyev was sentenced to two years of a "colony-settlement". In February 2010 his sentence was mitigated to two years of freedom restriction.[15]

Relatives of Magomed Yevloyev do not trust the official version. In their view, the owner of Ingushetiya.Ru was murdered intentionally. The family addressed the European Court on Human Rights with a complaint

COL. MAXIM SHAPOVAL

Ukrainian Military Intelligence

Shapoval was a part of the Chief Directorate of Intelligence, and Ukrainian media said he was chief of military intelligence’s special forces.

Col. Shapoval served 3 years leading special operations forces in combat missions in Eastern Ukraine, as commander of the 10th Special Detachment of the Main Directorate of Intelligence of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. The "ten" unit has the unofficial name of "Island", based on Rybalsky Island. Shapoval was the commander of a special appointment group, which in May 2014 retook Donetsk airport from pro-Russian separatists.

Col. Maxim Shapoval was instantly killed on the morning of June 27, 2017, when a bomb planted under the Mercedes Benz that he was driving exploded.

Prior to his assassination Shapoval was reportedly investigating Russia's military aggression in the ongoing war in the Donbass region for Ukraine's case against Russia in the International Court of Justice, also known as The Hague, Lb.ua said. Ukraine is currently suing Russia in the ICJ for “acts of terrorism and unlawful aggression.”

The Ukrainian government has been at war with Russian-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine since 2014. Many reports appear to show that Russia is funding and managing the separatists, but Moscow has repeatedly denied the accusations.